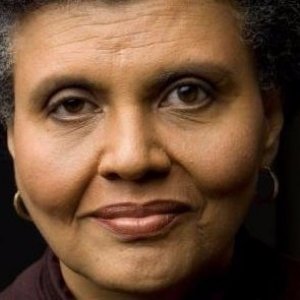

This month, #MEAction is honored to nominate Wilhelmina Jenkins as our Volunteer-of-the-Month. Wilhelmina has been fighting for recognition and progress for myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) for nearly four decades since she suddenly became ill in 1983. She brings a wealth of knowledge, wisdom and fortitude to our community, and we are incredibly grateful for her perseverance and dedication to people with ME through all these decades.

As an activist with #MEAction, she has been a key organizer with #MEAction Georgia, with #MEAction’s CDC Committee, and with #MEAction’s People of Color with ME Group. Read our interview below with Wilhelmina. Her story is compelling and heart-breaking, and her insights are invaluable.

What is your story with ME?

I became ill with ME/CFS in 1983. At the time, I was close to completing my PhD in physics at Howard University, was teaching physics at Howard and at the University of the District of Columbia, was in a research group at the National Bureau of Standards (now NIST) and was serving on committees to increase the number of minorities in physics. I was looking forward to a long, happy career teaching physics and doing physics research with my students. In February, 1983, I abruptly became horribly sick. All at once, I was in terrible pain. I became completely exhausted at the slightest effort. I couldn’t sleep. I got lost going to very familiar places. And, worst of all, I could no longer understand math and physics, even my own work. I thought that I was dying. I was terrified that my children, 13 and 7, would be left without a mother. My doctors were kind, but they had no clue what was wrong with me. In desperation I changed everything that I could think of – my job, my location, everything. But by 1987, I was completely disabled.

By this time, I was very depressed from all that I had lost. My family had moved to Atlanta in 1988 and I decided to see a psychiatrist because I knew that depression was treatable. By sheer luck, I chose a doctor who treated my depression, looked at the nightmarish symptoms that remained and asked me, “Have you ever heard of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome?” I had not. The 1988 meeting that defined the disease and gave it its horrible name had just met. (ME was not in use here at the time.) He sent me to an infectious disease doctor who confirmed the diagnosis and told me that there were no treatments. Bad news. But the good news was that I wasn’t alone. He connected me with the Atlanta support group and, for the first time, I met others who were gong through the same torture that I was experiencing.

How did you get involved in advocacy work?

I started doing advocacy on a small scale right away. These were the days when all we had was snail mail and telephones. I joined every national group that had a newsletter, starting with one of the first groups in Portland, OR. My name and phone number were placed on a contact list the CDC had published and I received calls from all over the country.

But, I became seriously involved in advocacy when, to my horror, my wonderful teenage daughter came down with this disease in 1991. I was shocked and furious. The government was treating this disease with no urgency at all. And the CDC was even saying that African Americans did not get this disease. There was a public meeting at the CDC which I and several of my support group friends decided to attend to attend. They convinced me to speak during that patient portion of the meeting. I haven’t stopped speaking out since.

How has advocacy work changed since you first began? What have been some of the highs and lows?

Without a doubt, the major change in how advocacy can be done has been the internet. After my first CDC meeting, I began to work in various capacities with the CFIDS Association of America, eventually serving on the board of directors until I became too ill to continue in 2000. Most of our meetings were held by conference call. Large packets of information had to be mailed out. Since almost everyone on the board was ill, we would be lying in our beds, trying to make the best decisions that we could about the direction that advocacy should take. The discussions were as vigorous as they could be, considering how sick we were! Every call-to-action, every piece of information distributed, was slow because of the limits of the technology of the time.

What has not changed is the commitment of people living with this disease to support each other and to demand that this disease be treated fairly by the government. Very sick people have always been willing to put their health at risk to do the work. My fellow advocates have always been an inspiration to me.

The high points for me have been the opportunities that I have had to speak out publicly about this disease. I have spoken in many places, ranging from a tiny radio station here in Atlanta to a congressional hearing during the old Lobby Days back in the ‘80s. One of the most interesting events was talking about this disease on the Oprah Winfrey Show with my daughter in 1998. My daughter and I were both wiped out, but we held each other up! I am a very shy person, but I have always felt that getting the information out, and also having people see that African Americans are affected by this disease like anyone else, was important enough for me to overcome my shyness.

One of the low points for me has been the antagonism that has been present for years between some groups of advocates, but I try not to dwell on that. I often quote my friend and longtime advocate Katrina Berne who said that the only sides in this struggle should be humans vs. the disease.

What made you want to get involved with #MEAction advocacy work?

Wilhelmina at the 2016 #MillionsMissing demonstration in Georgia.

Wilhelmina at the 2016 #MillionsMissing demonstration in Georgia.

I became involved with #MEAction following a series of conversations with co-founder, Beth Mazur. She suggested that I might like to try working with #MEAction. I was a bit reluctant initially – the community had just gone through a highly contentious period around the XMRV virus – but I trusted Beth enough to give it a try. It was clear to me very quickly that the people working with #MEAction were principled people working hard to achieve equity for our disease. I also felt that this was someplace that I could work to increase awareness of African Americans with this disease. I have participated in a number of committees since then. CDC has been an important issue for me, both because I am here in Atlanta and because our history with CDC has been so problematic. NIH is also important to me because our future depends on increasing the amount of good research into our disease. I try to participate whenever I think that I can make a contribution.

One of the major joys for me has been working with our state chapter, #MEAction GA. I have met a wonderful group of people who are intelligent, principled, and very willing to support one another. We have become close through monthly advocacy and support calls and through using the app Marco Polo to message each other and coordinate activities. With them, I regain much of the closeness I had with my old, in-person support group.

What advice would you give someone entering ME advocacy work?

To anyone just beginning advocacy, I would say, “Welcome to the struggle!” Back in the late ‘80s, we all thought that treatments and maybe a cure for this disease was only a few years away. This struggle has been longer and harder than any of us imagined. But for me, advocacy has been immensely rewarding. We are participating in making sure that this disease is treated with equity. We are fighting for our lives and the lives of those who come behind us. We will not stop until this disease is well-understood and treatable, and possibly curable.

I would also give a little warning. In #MEAction GA, we remind each other that advocacy can be seductive. Everyone involved in advocacy has had times when they have jeopardized their health by doing too much. Because cognitive disruption is one of my worst symptoms, I have to remind myself not to overdo it mentally – I will crash. But the good thing to remember is that this is not a rare disease. There are millions of us. If you need to step back to protect your health, there are many others who can step up.

What gives you hope?

Research gives me hope. I come from a family of research scientists. My mother, my father, my husband and I were all scientists. I know what science can do when the decision is made to address a problem with a sense of urgency. It’s difficult to explain how poorly executed the scientific effort toward this disease was in the past. Now, we have a number of research centers and individual scientists working hard and producing good work. We need many more – a disease with the impact of this one should have an army of scientists working on it. #MEAction and other advocates continue to work to make that happen. But knowing how much better the research is now gives me hope and confidence those coming behind me will have good treatments and that their dreams will not be crushed by this horrific disease. And that keeps me going.

) and a message about #MillionsMissing with your own networks. Desktop: Download by right clicking on the image or clicking on the download icon in the bottom right corner of the image. Mobile:

) and a message about #MillionsMissing with your own networks. Desktop: Download by right clicking on the image or clicking on the download icon in the bottom right corner of the image. Mobile: