“What makes activism work is [patients'] anger and fear...somehow you have to be able to capture that, put it in a bottle and bottle it and use it."

Larry Kramer

The following comes from a report produced by HCM strategists, a public policy advocacy consulting firm: “Back to Basics: HIV/AIDS as a Model for Catalyzing Change.”

What the AIDS movement accomplished

The legacy of the AIDS movement are staggering, unparalleled in any other disease:

- The U.S. government spends $3 billion per year in public funds for the research of HIV/AIDS.

- According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) there are now 33 drugs in seven classes developed and distributed by the 10 largest pharmaceutical companies in the world for the treatment of the disease.

- Most importantly, for those who are able to access treatment, AIDS, once a death sentence, is now a chronic disease.

Key accomplishments

- Patient-driven clinical trial designs: self-educated patient activists in conjunction with physician and scientist allies set the NIH agenda for research and clinical trials

- Expanded access to new drugs: AIDS activists, in a race to save their own lives, reduced regulatory hurdles to accessing drugs that might

- Congressional funding for research: Funding for AIDS research at the NIH increased from $5.6 million in 1982 to $1.62 billion in 1998. By 1998, AIDS research represented 12 percent of the entire NIH budget.

- Congressional funding for care: In addition to research, Congress also invested in services for prevention, care and assistance for people living with HIV. In 1990 it provided an initial $200 million. By 1994, Congress had allocated $632 milllion through this act.

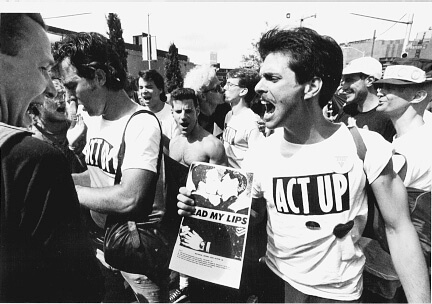

Grabbing Attention / Putting AIDS on the national agenda

HIV/AIDS activists were masterful in their ability to utilize the media and demonstrations to put a human face on the disease. They mounted demonstrations that offended people and made policy makers and federal officials uncomfortable.

- Civil disobedience: HIV/AIDS activists organized and engaged in civil disobedience to get the nation’s attention. It was an all-out ‘our bodies are on the line’ exercise. Never before had this country seen thousands of sick people laying their bodies down on Wall Street. Or chaining themselves to the fence of the FDA. Or storming the NIH. “You have to be able to inspire people at a level of civil disobedience,” noted Jim Curran, M.D., who was then the director of HIV/AIDS at the CDC. “Throwing condoms in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, I mean, who does these kinds of things? They were not afraid to get arrested.”

- Skillful use of media: ACT UP’s demonstrations were always an act of theater. They told a clear and gripping story because their core audience was the media.

HMC’s main takeaway in their study of what they call the “mass mobilization” and “theater” of the AIDS movement is a question: are present-day health movements too complacent, too polite?:

HIV/AIDS activists showed us that getting attention sometimes requires making people feel uncomfortable. Today, organizations are working to execute on multiple goals and may shy away from actions that make decision makers uncomfortable. Instead, they focus on building relationships and engaging in activities that make decision makers feel safe. They develop sophisticated strategies focused on how to work within the system and the rules, without challenging the notion that the system and the rules as constructed may not be in their best interest. And for individuals who don’t have organizations to work through, challenging the status quo may seem like a Herculean task.

Have we become complacent? In many instances, organizations meet with their elected officials, are invited to meetings at federal agencies, are asked to sit on advisory boards, and are often part of "the process."

And yet the level of frustration about the speed of getting new treatments and cures is growing. Access and face time do not mean you have decision makers’ attention...

Patients become experts

Once activists had garnered the attention to put AIDS on the national agenda, they began to focus in a more targeted way at specific goals, specific institutions, specific solutions. “The activists not only got attention effectively, they also did their homework and knew what to ask for.”

They stumbled across one woman named Iris Long who took them under her wing and served as a mentor. Larry Kramer remembers meeting Long — a housewife from Queens who was also a biochemist — for the first time. “She came to an ACT UP meeting and said ‘you really don’t know anything. You don’t know about the system. You don’t know about the drugs. You don’t know about the science. You don’t know how the government works. You don’t know the FDA from the NIH. You’re just out there yelling and screaming.’” She offered to teach this to anyone who wanted to learn, and a group of advocates, including Jim Eigo, took her up on the offer. From this, a group of highly informed advocates emerged.

AIDS activists became “patient experts” both in the political and bureaucratic processes in Washington and in the scientific process. While protests opened the door, their knowledge and the sophistication of their demands are what ultimately allowed them to become effective advocates for change.

“[The activists] were able to make us think in some new ways, to rethink some of the models that existed because the truth is some of the models were simply legacies of how things had been done but didn’t mean that that was the only way things could be done.”

Margaret Hamburg, M.D., assistant director at NIAID, 1989 to 1990,

The power of the ACT UP community

ACT UP created a structured setting for HIV/AIDS activists to come together and speak out in a unified office. They had many committees and there was a committee meeting virtually every night of the week. The committees allowed activists to get together, get to know one another, and create a sense that “they were all working together for the same cause.”

Kramer believes that one of the reasons that ACT UP was so successful was that it was social. He says, “It was a good time, which is something else that people should be aware of, that you should make whatever you are doing enjoyable. It helps cement brotherhood. And that’s important— brotherhood— in all of this.”

The ACT UP meetings were crucial in sustaining and focusing activists, allowing them to make meaningful connections, and creating a sense of fellowship.

ACT UP's Inside/Outside Strategy

“What ACT UP did so well,” recalls Peter Staley, “is that it had both an outside and an inside strategy.” As part of their inside strategy, clearly defined roles were created. Staley recalls that “there were the real nerdy geeks who just salivated over becoming experts on the most obscure minutia of immunology and virology. And then there were a few big picture people like me.” This combination of expertise created a powerful force.

Jim Eigo refers to this strategy as a “two-handed model.” He says that “we who were working on the inside never could have done what we did if we couldn’t deliver bodies in the streets. But bodies in the streets wouldn’t have gotten the regulatory reform in 14 months that people have been trying elsewhere to do over decades.”

Discussion

- What can we learn about the history of the AIDS movement?

- How can these lessons be replicated or translated for the ME movement?

- What are our constraints and what are our unique resources?

Cool!

That’s really impressive but I think too we need to be aware of how different the science was. People knew early on that this was an infectious disease and the HTLVIII/HIV virus was identified very early on. I’d just started a biochemistry degree at Oxford and there was a huge science buzz around Aids – there was nothing the hottest, most ambitious scientists wanted to work on more than that virus. There was a huge scientific interest driving research and demanding new funds.

Sure, at that stage there were no anti-viral drugs for any virus, and HIV was way more complex than any virus studied in depth at that time. But the tools of molecular biology were being developed, so scientifically it was a perfect challenge for the emerging technology.

AIDS activists were hugely impressive in the UK, as in the US – and it was wonderful to see how the NHS’s initial neglectful and prejudicial approach to patients was robustly, rapidly and effectively challenged by advocates. But when it came to the science, they were dealing with a much more helpful environment. I certainly wasn’t aware of patients/advocates setting the research agenda, or even of that being an issue, though I’m sure they had a huge impact on increasing funding.

Here and now, scientists are not queuing up to work on mecfs- quite the reverse.

Whereas we are often the opposite, frequently fighting among ourselves. Yet I’ve made several good friends via the online community. I wonder is there is some way to build that social side (I’m hopeless with facebook, I have to admit); forums generally – nothing to do with mecfs – can bring out the worst side of people, and I do wonder if some of our problems as a community is that it exists primarily online, without the face to face social contact that help builds a ‘brotherhood’, or sisterhood.

Another big stumbling block for us.

I think we can always learn from other movements, and few have been as effective as the Aids movement. But we have to see too how it differs from us, and work out our own solution.

Thanks for starting the discussion, Jen. And to Peter – your interview with him was a real eye opener for me.

Hi Simon – didn’t realize I could reply directly! See my more in-depth replies below.

Re: directing/pressuring certain directions in science, go to 7:17 in this video and replace “AZT” with “Ampligen” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vn8qEjPnoSo

Simon, I very much agree with what you say above. That is why I am a huge advocate for biomarkers being integrated into the definition.

And we have these biomarkers already. None are yes or no tests – I believe this illness is more like lupus, diagnosed with a combo of biomakers and symptoms.

Here are the ones I’m familiar with: low NK cell function; elevated titers of EBV/CMV/hhv-6, etc; R-NaseL; low Immunoglobulin IgG subclass 1 & 3; abnormal 24 hr stress test; POTS/NMH.

I realize though that this will leave a lot of people diagnosed with ME out in the cold though, as they don’t have these biomarkers. On the flip side, it will enable our illness to be taken more seriously, and move forward like the AIDS movement.

** And add abnormal cytokines to that list above!

hey simon,

something that is NOT convincing researchers to join our worthy cause is the wessely school amateur theatrics “PATIENTS ARE MEAN 2 ME!!one!”. clearly not mean enough, wessely hasn’t quite thoroughly fucked off as we were hoping he would all these years. it’s shitty double bind because anything loud, demanding or theatrical runs the risk of being labelled “hysterical”, “unbalanced”. they like to pull this one on women: try to advocate for yourself even passionately and suddenly you find yourself instructed to “calm down” “for your own good”.

Being a child of the sixties I saw lots of demonstrations. Maybe it is time to take a different look at how to accomplish our goals. I’m still conflicted on how to do this when we have a patient population that is so severely ill that to take part in something like this could mean a permanent slip backwards.

I was reading a book today and came upon this poem written by Langston Hughes, “Lenox Avenue Mural”:

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore-and then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over-like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

There are plenty of deferred dreams to go around and it has been feeling like a heavy load for much too long. Will we have to explode to get noticed? I guess time will tell.

Hi Simon! Thank so much for your reply. I think the scientific context being completely different is so interesting. Why is a new virus “hot” to scientists and a mysterious chronic illness not so much?

Regarding setting the research agenda, see ACT UPs document from the 1989 International AIDS Conference: http://oldmeaction.wpengine.com/?p=1611 In their protests they definitely asked for medical trials to be organized differently (e.g., including women and people of color as subjects), for research to focus not solely on the virus but also on treating opportunistic infections, and for a different process to allow for FDA approval of drugs – they needed to have evidence they were not harmful but the evidence for helping did not need to be as robust in order for it to be released to dying patients. They tried to modify research priorities so it was more focused on patients’ immediate needs.

When Kramer says ACT UP was social, he doesn’t mean people got along! On the contrary, there was LOADS of fighting. Watching How to Survive a Plague if anything normalized what we experience for me. There’s this great scene were people are screaming at each other in an ACT UP meeting and Larry Kramer starts yelling: PLAGUE, 50 MILLION PEOPLE INFECTED IS A PLAGUE! And still you behave like this?”

Peter also talks about the ACT UP / TAG breakup. It wasn’t pretty: http://oldmeaction.wpengine.com/how-to-keep-the-momentum-going-even-when-you-want-to-quit/

Anyway, the difference is I think that there’s a certain kind of more human, face to face interaction that forces people to confront each other as human beings, and that changes behavior. It’s much easier to be nasty or angry from behind a computer. It was in the context of close friendships and relationships that I imagine a lot of the best activism happened. That’s hard to recreate online – which is why I am hoping that regular video if not face to face conversation can be a part of the work we do here.

The bodies in the streets is definitely a problem but see: http://oldmeaction.wpengine.com/idea/should-me-activists-engage-in-civil-disobedience/ (I recently by chance met a projection artist! I have no time to gin up something like what they did in Spain, at least not at the moment, but it is a dream of mine.)

Debbie – unless you get massive numbers, perhaps the usual protest symbols and traditions really aren’t for us. They are too easily dismissed or drowned out. I think we need to get creative. We need us some guerrilla art. We need us some Banksy.

Also, I LOVE that Langston Hughes poem!

What they also had going for them was the fact that the LGBT community struggled and fought almost their entire life against prejudice, hate, neglect.

They had (have) a world apart from the hetero dominated world. And i must say this: they are a courageous bunch who know who they are and are willing to fight for recognition.

The ME community is rather ‘soft’ apart from a bunch of tenacious people (See twitter, See FB: the same names time and time again).

Other slogans, more agressive, more ‘in your face’, are certainly needed. An external PR company would be handy. So would be a big donation from a millionaire to set the Wheels in motion

For a long time now, I thought, “Why can’t we use the same tactics that the activists for HIV/AIDS used?” The big difference is the fact that Elizabeth Taylor and other Hollywood celebrities and popular bands and musicians got into the act. There were many LGBTs that were involved in Hollywood, and that disease hit very much “close to home.” I think that’s the big difference that made the government sit up and take notice. It was before the Internet and people had to get out and be heard – really seen and heard.

& with the internet, people only have to press a RT or ‘sign’ or ‘like’ button, but they don’t bother. I’d love to know why getting people onboard with an action is so difficult. unless, of course, we’re dissing CFSAC, everyone hates the CDC et al.